The rule changes are coming in 2023, and we'll have all offseason to discuss their impact on the fantasy baseball landscape. Quite frankly, we could do an entire week on just this topic and maybe cover every impact on our game. I personally feel the largest direct impact of the rule changes will be the welcome increase in stolen bases, with the combined factors of a larger base and limited pickoff moves squeezing both ends of the equation, as JJ Cooper of Baseball America pointed out in a tweet (and subscriber story) last week:

Everyone is going to spend the offseason talking about the pitch clock, but I wouldn't be surprised if it largely fades into the background by midseason once players adjust.

I predict the pickoff rules will have a bigger impact in 2023 and beyond.https://t.co/XJxuKhIoDz pic.twitter.com/ShOG0yeRtL

— JJ Cooper (@jjcoop36) September 9, 2022

My focus today is going to be on looking at players who could benefit due to the changing of the shift rules.

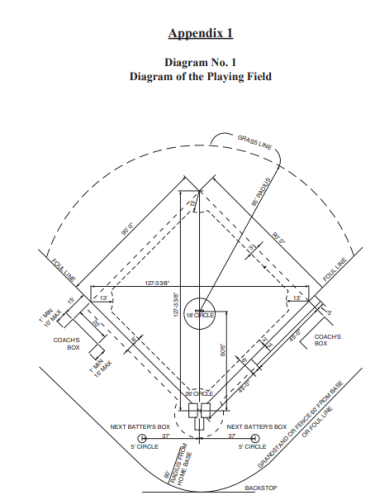

The new rules state that all four infielders must have both feet entirely on the infield dirt when the pitcher is on the rubber and that two infielders must be entirely on either side of second base when the pitcher is on the rubber. Failure to do so will result in an automatic ball. Teams will not be able to employ groundskeeping gamesmanship as the Giants did in 1962 when they turned the area around first base into a swampy bog

The rule changes are coming in 2023, and we'll have all offseason to discuss their impact on the fantasy baseball landscape. Quite frankly, we could do an entire week on just this topic and maybe cover every impact on our game. I personally feel the largest direct impact of the rule changes will be the welcome increase in stolen bases, with the combined factors of a larger base and limited pickoff moves squeezing both ends of the equation, as JJ Cooper of Baseball America pointed out in a tweet (and subscriber story) last week:

Everyone is going to spend the offseason talking about the pitch clock, but I wouldn't be surprised if it largely fades into the background by midseason once players adjust.

I predict the pickoff rules will have a bigger impact in 2023 and beyond.https://t.co/XJxuKhIoDz pic.twitter.com/ShOG0yeRtL

— JJ Cooper (@jjcoop36) September 9, 2022

My focus today is going to be on looking at players who could benefit due to the changing of the shift rules.

The new rules state that all four infielders must have both feet entirely on the infield dirt when the pitcher is on the rubber and that two infielders must be entirely on either side of second base when the pitcher is on the rubber. Failure to do so will result in an automatic ball. Teams will not be able to employ groundskeeping gamesmanship as the Giants did in 1962 when they turned the area around first base into a swampy bog to inhibit stolen base attempts by Maury Wills. The baseball rule book is very explicit in the dimensions of the infield and how far that dirt line is from the pitching rubber in Appendix 1 of the rulebook:

This means that a team could employ a two-man outfield if it wants to take the chance a hitter will not hit an opposite-field line drive or flyball that would easily become a double if not a triple should they want to employ an overshift to the pull side. Shifting was once an anomaly that dated all the way back to when Lou Boudreau first employed it as a player-manager when Cleveland played Boston in 1946 to frustrate Ted Williams. Nowadays, every team employs the shift, from the Jays leading the league by shifting 53 percent of the time to the Rockies bringing up the rear at just 19 percent of the time.

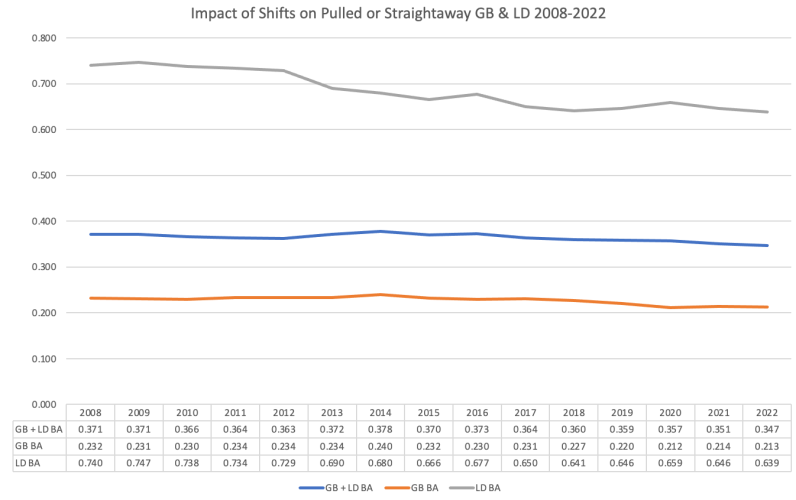

The shift is used because it works against the hitters it is designed for. Teams wouldn't be shifting 34 percent of the time on the whole if the strategy didn't work. The batted ball results on groundballs and line drives on batted balls straightaway or pulled show how the increase of shifting has impacted those events since 2008:

When we combine the data sets, we find that it has become 7 percent more difficult to convert such batted balls into hits in 2022 than it was in 2008. If we isolate to just groundballs above, it has become just over 8 percent more difficult to turn those into hits. However, the larger penalty has been on line drives, as it has become nearly 14 percent more difficult to turn a pulled or straightaway line drive into a base hit. The higher quality of contact has been the most penalized in this overshifted era, as teams can position infielders perfectly aligned to spray charts against certain archetypes. The league is choosing to put a stop to such strategy as they want more offense, so they are putting an end to many of the defensive alignments we have seen where a well-struck ball to the right side sneaks past the natural second base spot, but someone positioned in shallow right is able to get to the ball and throw out the runner. This has become a larger issue on batted balls up the middle, as the league has seen batting average on straightaway grounders and line drives fall from .449 in 2014 to .361 this season, resulting in a 19.6 percent decline in the likelihood of batted balls up the middle becoming hits.

As a fan I'm all for the shift, because it is strategy and I am not for taking away a team's ability to use legal strategies on the field if they are willing to accept the consequences of their shifting. Teams will still be able to place a shortstop or second baseman right next to the second base bag as the pitch is being delivered. Those infielders can then aggressively move to their previously desired position should they choose to. My larger concern is the unintended consequences for the hitters who tend to use all parts of the field who are now being penalized by the league as they look to cater to those who lean into a pull-heavy power-hitting approach. I digress...

Using xBA-BA a a measure, the table below shows the hitters whose actual batting average is at least 100 points worse than their expected batting average:

HITTER | BA | xBA | xBA-BA |

0.193 | 0.389 | 0.196 | |

0.196 | 0.354 | 0.158 | |

0.203 | 0.346 | 0.143 | |

0.288 | 0.423 | 0.135 | |

0.220 | 0.350 | 0.130 | |

0.276 | 0.394 | 0.118 | |

0.279 | 0.396 | 0.117 | |

0.255 | 0.368 | 0.113 | |

0.317 | 0.430 | 0.113 | |

0.278 | 0.390 | 0.112 | |

0.274 | 0.382 | 0.108 | |

0.331 | 0.439 | 0.108 | |

0.303 | 0.408 | 0.105 | |

0.241 | 0.345 | 0.104 | |

0.293 | 0.396 | 0.103 | |

0.275 | 0.378 | 0.103 | |

0.279 | 0.380 | 0.101 |

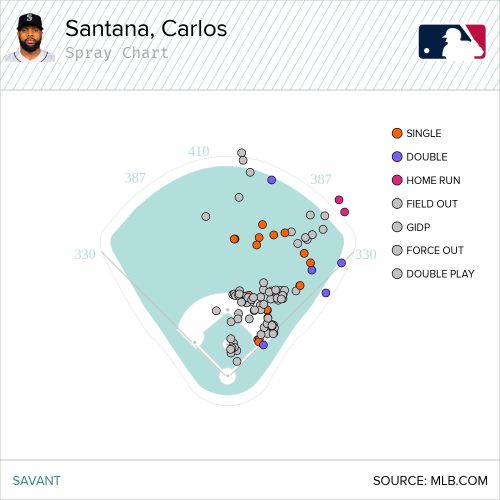

Santana is an interesting leader on this board because he is hitting .200/.317/.392 on the season despite lofty run production since his move to Seattle. He has 15 homers, 29 runs, and 36 RBIs in 64 games with Seattle despite a .186/.288/.436 line, as he had made the most of his homers while getting absolutely punished by the shift. He has hit just one baseball to the non-pull side of the field this season (and most seasons) as has generated a high volume of batted-ball outs into shifted alignments:

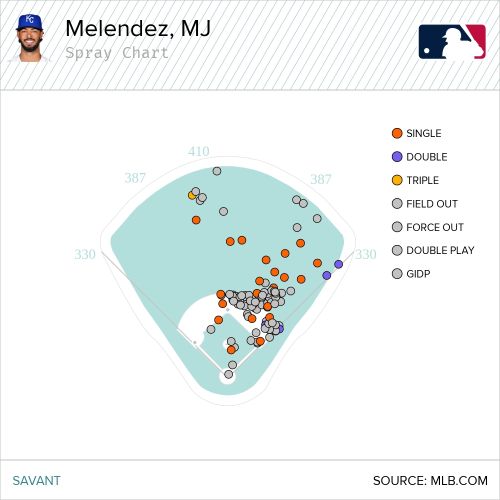

Santana is halfway to age 37, so he would still need to make quality contact in order to get grounders or liners through the new rules, but who's to say opposing teams won't take the left fielder and position that player in short right field if the club had rangy players in center and right field? I could easily see the Rays entrusting Jose Siri and Manuel Margot to cover the outfield and moving Randy Arozarena to short right field for a hitter such as Santana. Santana's former teammate, MJ Melendez, has a very similar spray chart but with enough of a tilt to the other field where defenses would not be so quick to employ a two-man outfield:

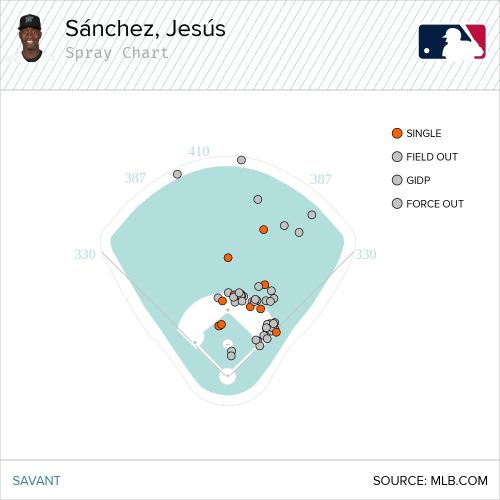

Jesus Sanchez has been a big disappointment this season, but he too has been his own worst enemy, with a near refusal to use the other half of the field:

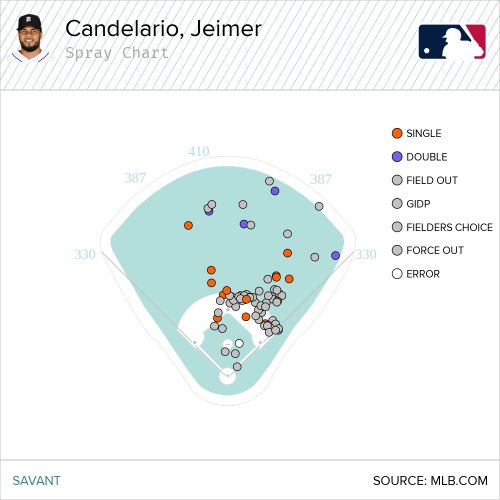

The new shifting rules will not exactly turn this former prospect into a goldmine next year as his spray chart is still rather defensible under the new restrictions. I am more interested in someone like Jeimer Candelario, who has been a tremendous disappointment after two positive seasons in Detroit as he has tried to hit his way through his struggles with little success. He at least shows more tendencies to use a little more of the field, so defenses would aggressively play him up the middle at their own peril.

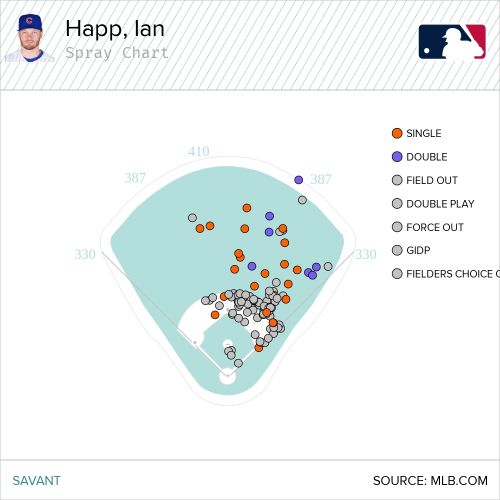

Ian Happ (when hitting lefty) would be another hitter who should benefit from less shifting, with some more openings on the infield and no more shallow right fielder. He does spray the ball all over the right side, so he should be tougher to stifle in a more traditional lineup, and his spray chart doesn't exactly scream for a two-outfielder alignment except in the most extreme situations:

Conversely, there are a few names who are vastly overperforming their expected batting average this season on shifted alignments with grounders and liners who may run into some issues next season:

HITTER | BA | xBA | xBA-BA |

.431 | .370 | .061 | |

.425 | .367 | .058 | |

.413 | .362 | .051 |

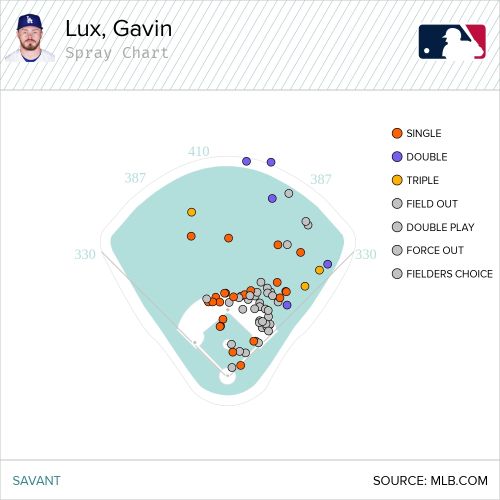

Lux has had quite a few hits up the middle against shifted infield alignments this season which could disappear next season under the new rules should his spray chart tendencies hold up.

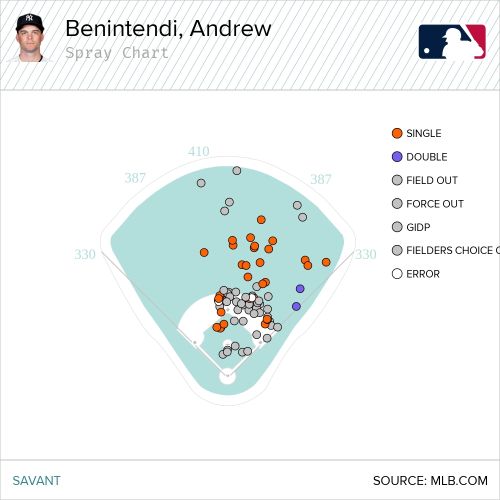

Likewise, Benintendi has a similar spray chart, as he has several infield hits to traditional defensive spots. He was having a surprisingly nice season until he was traded to New York:

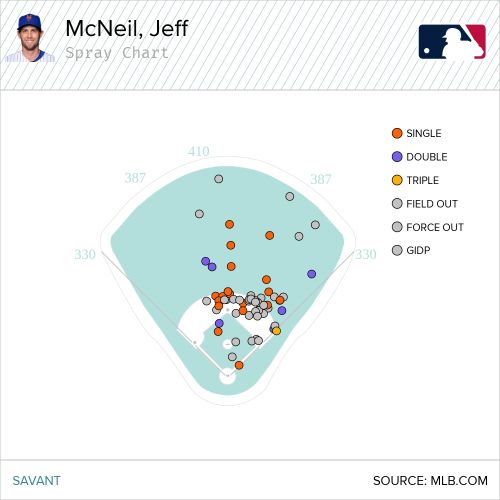

Finally, Jeff McNeil has had quite a few infield hits, including a double on a ball that touched the infield grass before reaching the dirt at the traditional shortstop position. A more standard defensive alignment could punish him as much as it rewards some of the hitters mentioned earlier in this article:

We are honestly only scratching the surface on the impact the new rule changes will have on fantasy projections and production for 2023. This is not a one and done topic, so expect to read and here more about it all throughout this offseason. I'm a fan of some of these changes, but the limitations on shifting is something I do not like out of hand, though I want to see how it plays out before passing full judgment. As Milton Friedman told us, "One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results."